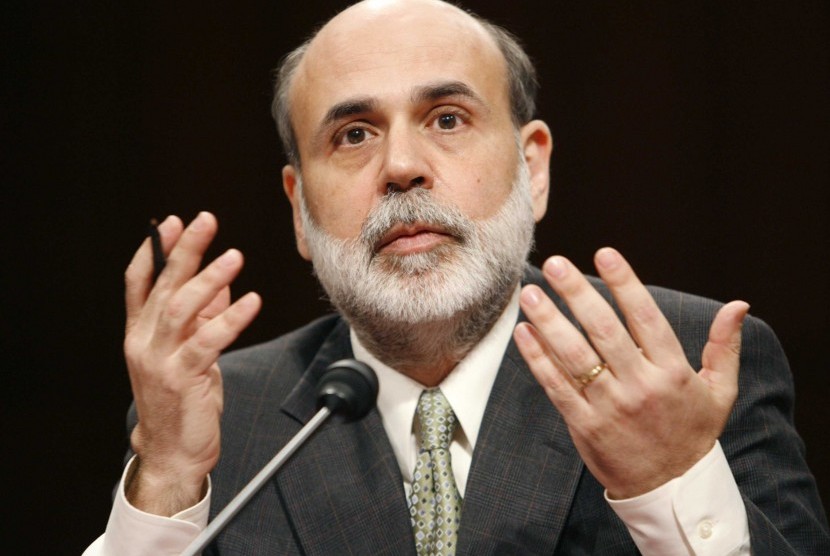

REPUBLIKA.CO.ID, WASHINGTON -- In his final performance, Ben Bernanke rewrote the script.

Investors had been on edge for months about when the Federal Reserve might slow its economic stimulus. A pullback in the Fed's bond purchases, they feared, could jack up interest rates and whack stocks. Bernanke's mere mention of the possibility in June had sent stocks tumbling.

So on Wednesday, Bernanke showed something he'd learned from leading the Fed and addressing the public for eight years: Tough news goes down best when it's mixed with a little sweetener.

At his last news conference as chairman, he explained that the Fed would trim its monthly bond purchases by $10 billion to $75 billion — a prospect that had worried the markets.

Yet Bernanke also calmed nerves by walking back a plan to consider raising short-term rates once unemployment reaches 6.5 percent from the current 7 percent.

That 6.5 percent threshold the Fed had been using? Not much of a threshold anymore. The Fed now says it expects to keep its key short-term rate near zero "well past" the time that unemployment falls below 6.5 percent.

The message: The Fed expects low-cost loans to boost the economy for, well, for a very long time.

Investors rejoiced by sending the Dow Jones industrial average rocketing nearly 300 points to a record high.

It means that five years after the Fed responded to the financial crisis by cutting its key short-term rate to near zero, it has no plans to change course. Low rates encourage spending, hiring and investing. At the same time, critics say it can inflate dangerous bubbles in stocks, housing and other assets.

Bernanke's remarks suggested that three factors had led him to the balance he struck Wednesday: The unemployment rate can be misleading. The Fed wants to avoid setting unrealistic expectations. And inflation remains so low that it poses a potential problem for the economy.

"It comes out of the danger that you're getting so specific with these unemployment rates, you end up in a situation where you put yourself in a corner," said Wells Fargo chief economist John Silvia. "Sometimes you can be too specific and too transparent, certainly in the uncertain world of economics."

With the Fed essentially dropping the 6.5 percent unemployment threshold, Bernanke signaled that he now sees greater public transparency — a longtime priority of his as chairman — as being somewhat flawed. It also means his likely successor, Janet Yellen, will feel at liberty to show similar flexibility.

Though the Fed will be scaling back its monthly bond purchases, Bernanke called the buying of Treasurys and mortgage bonds merely a "supplementary tool" compared with the "main tool" of the Fed's benchmark short-term rate.

At his December 2012 news conference, Bernanke had announced the 6.5 percent unemployment threshold as a way to "allow the markets to respond quickly and promptly to changes" in Fed policy and act "like an automatic stabilizer."

"We're transparent about what's going to determine our policy in the future," Bernanke said then.

But over the past year, the decline in the unemployment rate to 7 percent from 7.8 percent hasn't necessarily reflected a much stronger job market. So Bernanke adapted.

Unemployment has fallen in part because the equivalent of more than 7 million Americans left the workforce and were no longer counted as unemployed. Some of this reflects an aging population. Some of it comes from a discouraged group of Americans who can't find jobs. All of it suggests an underlying weakness in the economy.

"We want to look at hiring, quits, vacancies, participation, long-term unemployment," Bernanke said Wednesday. "So I expect there will be some time past the 6.5 percent before all of the other variables we'll be looking at will line up in a way that will give us confidence that the labor market is strong enough to withstand the beginning of increases in rates."

Most Fed officials now expect unemployment to drop to 6.5 percent by the end of next year, according to new projections released Wednesday. Many projected that rates would increase starting in 2015 — seven years after the financial crisis erupted.

Secondly, more transparency has not stabilized the markets. The stock sell-off that occurred in June after Bernanke suggested that bond purchases could soon end eventually turned into a rally. After the Fed chose not to pull back on its buying at its September meeting, stocks set record highs.

Instead of stabilizing the markets, Bernanke's specifics had created a yo-yo effect. Economist Stanley Fischer, who taught Bernanke at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, warned that overly specific forward guidance had made financial markets more volatile.

A former governor at the Bank of Israel who is expected to be nominated by President Barack Obama to become the Fed's vice chairman, Fischer believes that rates should be determined by a series of economic conditions that are hard to forecast.

"We don't know what we'll be doing a year from now," he said at a September conference in Hong Kong. "It's a mistake to try and get too precise."

And, lastly, there is the trouble created by low inflation.

The Fed's dual mandate is to maximize employment and provide stable prices. But inflation as measured by the index the Fed monitors has been only about half the central bank's 2 percent target this year.

Some Fed officials forecast that inflation could stay below their target through 2016. The word "inflation" was mentioned 86 times during Bernanke's news conference.

When prices are flat or even decline, consumers might become reluctant to spend because the costs could be cheaper a week, a month, or even months from now. It's a sign that demand is too weak to spark much growth. The Fed can pump money into the economy through lower interest rates to keep inflation at a reasonable level.

"There is still this question about inflation, which is a bit of a concern, more than a bit of a concern," Bernanke said. "We take that very seriously. And if inflation does not show signs of returning to target, we will take appropriate action."